Four—have recovered the Land—

Forty—gone down together—

Into the boiling Sand—

Ring—for the scant Salvation—

Toll—for the bonnie Souls—

Neighbor—and friend—and Bridegroom—

Spinning opon the Shoals—

How they will tell the Story—

When Winter shake the Door—

Till the Children urge— [Children ask]

But the Forty—

Did they—come back no more?

Then a silence—suffuse the story—

And a softness—the Teller's eye—

And the Children—no further question—

And only the Sea—reply—

Fr685 (1863) J619

I picture Dickinson performing this rollicking ballad to an intimate audience that included children. I vaguely remember from long ago studies that poetry readings were fairly popular Victorian entertainments, and that would be particularly true in educated communities such as Amherst.

This ballad, however, does more than tell a tale: it goes on to describe a setting for and the anticipated response to the tale telling. As the perspective changes, so does the tone – and meter here drives the tone. A bit of scansion reveals how.

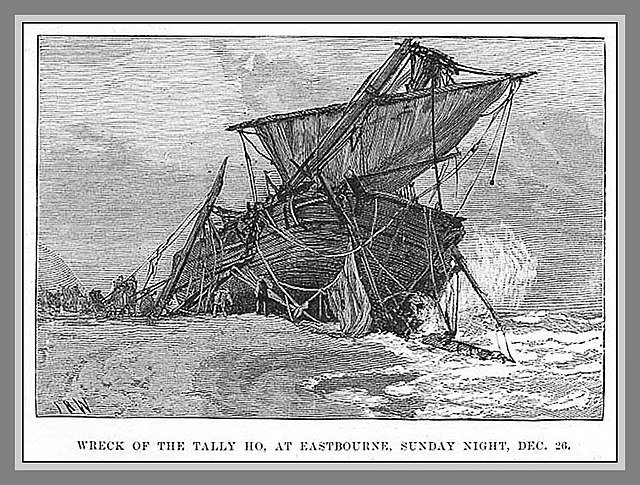

The first two stanzas describe a tragedy at sea caused by a ‘great storm’ where four people were saved but forty lost – ‘gone down together – / Into the boiling Sand –’. The lines ring out with dactyls (DA da da) followed by trochees (DA da). Tennyson famously used similar meter in his famous 1854 ballad “The Charge of the Light Brigade”. In Tennyson’s poem the dactylic rhythm suggests the galloping of the horses as they ride to the hell of battle. In Dickinson’s it is the punishing winds and waves that doom the ship and most of its passengers.

|

| Wreck of the Tally Ho, Josiah Robert Wells, 1887 |

The final stanza’s lines softly rock like the quieted sea in their use of anapest followed by iambs. The whole stanza is sibilant with ‘s’ sounds: The children are silenced, the Teller softened, and the only the Sea replies. And yet, despite its swishing murmurs and rolling crashes, the Sea reveals nothing.

To live by the sea is to know the Glee (and what an amazing word to start the poem) but also the drowned, the tolling bells. The children soon learn to offer “no further question”.

Here are a few narrative ballads that Dickinson would probably have been familiar with:

‘The Sands of Dee’, Charles Kingsley, 1850

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1834) Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Paul Revere’s Ride, (1860) Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Lady of Shalott, (1842) Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Good to see a new post! And on a subject that feels timely with Gordon Lightfoot's obituary this week speaking about his ballad on the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

ReplyDeleteAgree with J Wilton. So great to read a new post. Love the points you made on her changes in meter. Brought here to (re)read your discussion of To Hear an Oriole Sing, as I heard my Baltimore oriole singing (divinely) outside in Delaware this morning.

ReplyDeleteWellcome back!!

ReplyDeleteDelighted, no, overjoyed to find a new post!

ReplyDeleteI just found your blog! I hope that you are well, and that more posts are comings!

ReplyDeleteI came across this terrific video presentation for HS seniors on this poem. It has a couple great observations in it.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.google.com/search?q=dickinson+shipwreck+poems&rlz=1CAKVWL_enUS1029&oq=dickinson++shipwreck+poems&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigATIHCAIQIRigATIHCAMQIRigAdIBCDQ4MDBqMGo0qAIAsAIB&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:c137674d,vid:D0WElLkLSiw,st:0